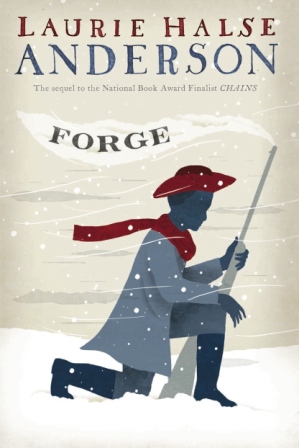

Forge

Laurie Halse Anderson

An escaped slave enlists as a soldier and struggles with his regiment to survive the bitter cold winter of 1777-78 in Valley Forge. Still a teen, Curzon must endure days without food, disentegrating boots, disrespect and mistreatment by his fellow soldiers. He is fighting for the freedom of people who will not recognize his own rights, and who intend to keep loved ones enslaved. The British, he has heard, have promised to free any slaves who fight for their side. But in the harsh conditions of the Valley Forge military camp, Curzon discovers friendship, loyalty and the strength to pursue his dreams.

More about Forge at Goodreads.

Learn more about Laurie Halse Anderson.

Mind Boggling

Georgia Blizzard

Born in 1919 of Irish and Apache heritage, Georgia Blizzard began making pottery as a child with clay found in local Appalachian streams and hillsides. She is a self-taught artist and all her pieces are formed by hand. Of her artwork and its creative process, she stated, “I can get rid of taunting, unknowing things by bringing them out where I can see them . . . I feel the need to do it.”

More about Georgia Blizzard.

Healing Quote of the Day

If good things lasted forever, would we appreciate how precious they are?

― Bill Watterson, Calvin and Hobbes, It’s a Magical World

Dog and Butterfly

Heart

See the dog and butterfly

Up in the air he likes to fly.

Dog and butterfly

Below she had to try

She roll back down to the warm soft ground, laughing

She don’t know why, she don’t know why

Dog and butterfly.

More music by Heart

Post by SuperKevinHeart

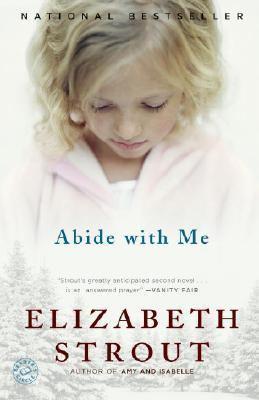

Abide With Me

Elizabeth Strout

In the late 1950s, in the small town of West Annett, Maine, a minister struggles to regain his calling, his family, and his happiness in the wake of profound loss. At the same time, the community he has served so charismatically must come to terms with its own strengths and failings–faith and hypocrisy, loyalty and abandonment–when a dark secret is revealed.

In prose incandescent and artful, Elizabeth Strout draws readers into the details of ordinary life in a way that makes it extraordinary. All is considered–life, love, God, and community–within these pages, and all is made new by this writer’s boundless compassion and graceful prose.

From Goodreads

In the Realms of the Unreal

Henry Darger

Henry Darger (1892-1973) was born in Chicago and placed in a home for boys after his mother died and his father became too ill to care for him. As a young teenager, Darger was diagnosed with behavioral issues and institutionalized in the Lincoln Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children. He was forced to perform labor until he escaped a few years later at the age of 16. He lived quietly and worked as a custodian until his death at the age of 81, when his 15,145-page, vividly illustrated manuscript of the Vivian Girls and their adventures in the Realms of the Unreal was discovered.

View more artwork by Henry Darger at the American Folk Art Museum.

I Shall be Released

Music Saves

I Shall be Released by Bob Dylan. Another performance by the VAMS Music Saves Project. The Vancouver Adapted Music Society (VAMS) supports and promotes musicians with physical disabilities.

See the previous VAMS post on Healing Hamlet.

To learn more about VAMS visit vams.org.

Post by SSDFoundation.

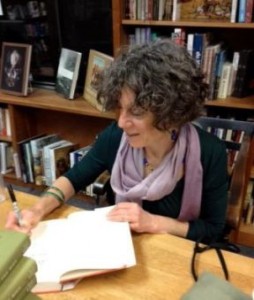

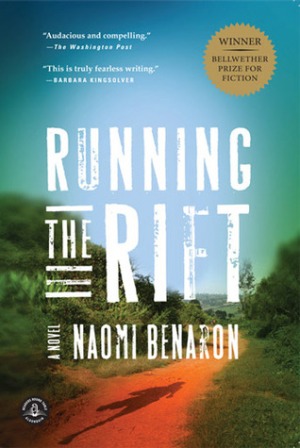

Author Naomi Benaron

An Interview with the author of Running the Rift

The best advice I can give is to never let your rational mind get in your way. If you move forward one step at a time you will likely get where you want to go, and even if you don’t, the journey will teach you much.

The child of two psychiatrists, Naomi Benaron was born in Brookline Massachusetts and raised in Newton, not far from the Boston Marathon course she would complete years later. Earning degrees from both MIT and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, she worked for many years as a seismologist and geophysicist before deciding to get her MFA in Fiction from Antioch University in Los Angeles. A self-described gypsy at heart, Naomi has lived in a kibbutz, crewed on charter sailboats, worked on a shrimping boat, and continues to enjoy trips through Europe and East Africa. She has run marathons and competed in Ironman triathlons and finds training as necessary as breathing and eating. Naomi’s short story collection, Love Letters from a Fat Man, won the 2006 Sharat Chandra Prize for Fiction and her stories and poems have appeared in numerous literary journals. Naomi currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, with her husband, Dan Coulter, and their two dogs, Scout and JillyRoo. When not writing or training, she teaches online courses for the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program and mentors Afghan women in the Afghan Women’s Writing Project. Her first novel, Running the Rift, won the 2010 Bellwether Prize for Fiction, an award given for literature that addresses issues of social justice. Naomi took time with Healing Hamlet to talk about the book, the events which brought the story to life, healing from trauma and pushing boundaries.

You are a scientist, an experienced seismologist and geophysicist, and an award winning fiction writer. Not everyone can claim success in both “left brain” and “right brain” fields. Which came first for you, your interest in science or storytelling? Which comes easiest to you?

What came first and what is most deeply rooted in my soul, as it were, is writing. It comes so much more easily than science. Science I have to work at, to beat into my head with a blunt object. I will always love the logic and the dance of things scientific, and this will always be part of my writing, but I could never go back to being a scientist. Solve a differential equation or transform inertia tensors? No thanks.

Your book Running the Rift explores the forces leading up to the horrific 1994 genocide in Rwanda. You first visited that country in 2002. How did you come to be there? When did you know you would tell the story of the boy runner, Jean Patrick Nkuba?

My first trip to Rwanda came about through a series of coincidences or, as I like to think of it, gentle pushes of fate: Beshert, we say in Yiddish. I had the opportunity to meet a runner from Burundi which I mentioned to my dog trainer, Maureen Odenwald. Maureen replied that she loved Rwanda and had been invited to the 90th birthday party of Rosamond Carr, an American ex-pat who had an orphanage for child survivors of the genocide. She said she didn’t want to go alone, so I volunteered to go with her. I began falling in love with the country when I saw it rise up beneath the wings of our plane. I have never stopped falling in love with Rwanda. That first visit, I went for an early morning walk on the shores of Lake Kivu and found human bones and teeth in the sand. Holding them in my hands, I realized that they were more than bones, they were stories. If someone didn’t tell the stories, they would be forever lost. I already knew I was going to write a story about an East African boy (he started out as a swimmer in Burundi). And so, the story morphed from there and Jean Patrick was born. He rose from the water and began to run.

Since getting to know the country and people of Rwanda, what do you believe are the steps in healing from such incomprehensible trauma?

That is a really difficult question. Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, has done a remarkable job, I think, in addressing the root causes of genocide: ignorance and poverty. He has put a great deal of emphasis on education and health care, and he is really working on bringing economic independence to the country through tourism, NGOs and micro-industries. As an athlete, I am really encouraged by the national teams of Rwanda, in particular their bike team. There are several articles by Philip Gourevitch on reconciliation and in particular about the bike team, and I find them most uplifting. I think when you are training with someone—sweating and suffering and growing—identity becomes more about team than about religion or ethnicity or political party. Seeing the other side of the coin is Jean Hatzfeld in his article Together Again, published in the Paris Review. He is much more pessimistic about healing. I think forgiveness is key. If there is to be healing, it must start with recognition of the transgressions and from there progress toward asking forgiveness.

Your mother lost many family members and loved ones in the Holocaust. After World War II ended, the United Nations adopted The Genocide Convention to prevent future atrocities. “Never again” was the global response. And yet the world has stood by while mass killings have occurred in Bangladesh, East Timor, Cambodia, Guatemala, Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur… You are a self-described social activist, choosing “the power of the written word to effect change”. What do you believe the average human can do to help prevent these atrocities around the world?

Wow! That’s a tough one. I think it starts with recognizing our shared humanity. The first step on the slippery slope to genocide is “othering,” making distinctions between yourself and someone else based on ethnicity, religion, the color of your hat – whatever. Once we start understanding that we all share the same needs and desires, the same wishes for the future, it becomes more difficult to demonize a particular individual or group. And then there is always the option of contributing to good causes, raising awareness of atrocities on a personal level, volunteering for an organization – things like that. Or you can write an article, a poem, a novel.

Did your experience as a long distance runner help provide the needed discipline to complete a novel?

Absolutely! Training has influenced all aspects of my life in a positive way. Running a marathon or doing an Ironman makes you realize that everything proceeds one step at a time. Although I often lose sight of this, writing a novel proceeds by the same slow process.

Your life thus far has been an example of redefining limits. You are a marathon runner, an ironman triathlete, a scientist and a poet and fiction writer. As an American who didn’t live through the atrocities, you were able to pen an authentic fictional account of the Rwandan genocide. Where do you find the courage and drive to set and achieve the goals in your life? What advice would you give to those who want to push their own boundaries?

Thank you. Another interesting question! I owe much to my mother who was a rebel and a fighter her whole life. I just follow her example. I am not a courageous person; in fact, I’m a big chicken. I just make it a point of forcing myself to do things I am terrified of doing. This involves a healthy dose of stupidity, but the result is that I travel to places I would never otherwise get to experience. The best advice I can give is to never let your rational mind get in your way. If you move forward one step at a time you will likely get where you want to go, and even if you don’t, the journey will teach you much.

You teach writing courses through the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program. What is the most important thing you want your students to learn?

Write from your heart. Tell the story that is beating at the walls of your chest and that needs to find voice.

You mentor Afghan women through the Afghan Women’s Writing Project (AWWP). What can you tell us about this project and how you got involved?

The AWWP is a project started by journalist and writer Masha Hamilton. It exists to give voice, support, and affirmation to the women of Afghanistan. There are online “classrooms” where these women share work with a mentor with the goal of polishing pieces and posting them in the AWWP journal. (We encourage visitors and comments!) Part of the project is to provide a physical space where the women can meet in safety to exchange work, find inspiration, and get to know each other. The project also attempts to provide computers and thumb drives to as many women as possible. I got involved when I read an article about them in a local journal.

What is your next literary project?

I am writing a novel about three generations of Holocaust survivors: a grandmother who survived Terezín and Auschwitz, her daughter, and her granddaughter. It involves hip hop, art as defiance, and Verdi’s Requiem.

Anything else we should know about you?

My husband, Dan, has been tolerant of my insanity for 25 years. During that time, he has been an anchor and cooked many delicious meals. My dog Scout is a published poet. My dog JillyRoo is happy just being a dog. As for me, my suitcase is always packed.

Learn more about Running the Rift and Naomi Benaron on her website.