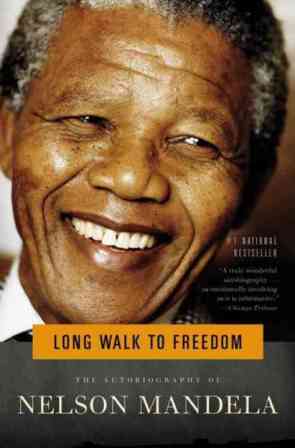

Long Walk to Freedom

Nelson Mandela

No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.

Find Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela

In My Own Light

Kathy Jones

My hope is that people who see my work are moved to bring their own history to the painting and to tell their own stories.

Visit the website for artist Kathy Jones

Poet and Author Helen Frost

For me, still, each novel emerges from careful attention to language, including the form, the sound, and the imagery, things I first learned through poetry.

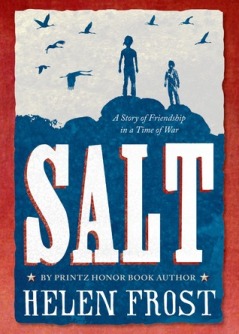

Born in Brookings, South Dakota, Helen Frost grew up as one of ten children, in a supportive, close-knit family. From her earliest memories, her parents nurtured her natural curiosity in the world around her, which would later emerge through her poetry and stories. She received a teaching degree from Syracuse University which opened up a whole new world of adventure and travel. She has taught children in England, Scotland, Vermont, Indiana, the remote Alaskan village of Telida, and a juvenile detention center in Fort Wayne. An author of many nonfiction children’s books about science and nature, Helen published her first novel in verse, Keesha’s House, in 2003. Over the years, Helen’s poems and writings have received numerous awards. Her most recent book, Salt: A Story of Friendship in a Time of War

, was published in July of 2013. Helen Frost has two grown sons and currently lives with her husband in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Helen, thank you for taking time to visit with Healing Hamlet. Can you remember the first poem you ever wrote? What was it about? When did you first realize the power of words and that your own words might have an effect on others?

I did love putting words together on paper when I was a child. Even before I could read and write I liked to scribble in lines across paper, pretending to write. I remember, at about age four, playing outdoors with a friend, we invented a game that involved pounding leaves with a rock to make it look like writing, then delivering this “letter” to someone, probably one of our sisters or mothers. Such primitive, and yet oddly literary, play.

The first poems I wrote were pretty silly, but I took them seriously enough to give them to people as gifts. When my grandmother died, my mother discovered that she had kept a poem I sent her when I was about eleven.

You grew up in a small city, supported and nurtured by a large, family. But you had a restless side that led you to teach in England and Scotland, live in a tent on a Scottish isle, work a summer job in McKinley (Denali) National Park, and spend three years in a remote Alaskan village. How did these experiences enrich your life and your writing?

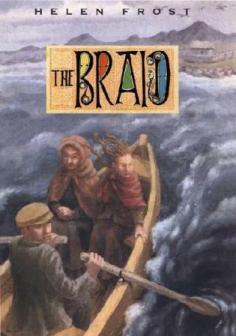

Each place I’ve lived is still very much part of my “mental landscape” and all these different places come back to me when I’m writing. One example is The Braid

Each place I’ve lived is still very much part of my “mental landscape” and all these different places come back to me when I’m writing. One example is The Braid, set on an island on the west coast of Scotland. I camped on the island of Mingulay, now uninhabited, about 30 years before writing The Braid. When I visited again, as part of my research for The Braid, I found that my memory of the island was very accurate. There were stone houses that had been abandoned in 1912, and I thought a lot about the life of this little community when I first camped on Mingulay. I loved spending time there in my imagination, and learning more about it to fill in the details of the story.

You have been teaching all of your adult life. Your books, Spinning Through the Universe: A Novel in Poems from Room 214 and When I Whisper, Nobody Listens: Helping Young People Write About Difficult Issues come directly from your experiences in teaching and mentoring children. What has been the most important thing you’ve learned from your students?

Spinning Through the Universe will be reissued in paperback in March 2014, with a new cover and a shorter title: Room 214: A Year in Poems. I’ll give an example from that book of something I learned from children that became important in my writing. I was friends with a family which included a boy with cerebral palsy, severe enough so that he couldn’t do everyday things like blowing out birthday candles. He was very smart, as was his younger sister, and they told me about the invention of the hairdryer-contraption that could blow out birthday candles. I asked their permission to include it in the book, and they were happy to give it. When I speak in schools now, I love letting children know that there is a real invention behind that poem, and that it worked!

You have worked with youth impacted by violence. How does writing poetry promote healing after trauma?

I recently had a note from a girl I met in 1998 when I was part of a project to help young people write about violence. She was 14 then, and is 33 now, happily married with two children. She wrote: I want to thank you for what you did for all of us in high school. I had no hope but you made me see that something good can come of something bad… Thanks again for everything. You coming to our school had changed my life completely and I would not be where I am today if I had not written that story.

I do a lot of preliminary work to create a safe place for these stories before anyone begins writing. It’s hard to say exactly how this works, but somehow, being able to write something down and have it received and respected, does make a big difference.

Your novels cover a wide range of characters who must navigate personal hardships or tumultuous historical events. How did you come to know these characters and to realize that you could tell their stories?

Your novels cover a wide range of characters who must navigate personal hardships or tumultuous historical events. How did you come to know these characters and to realize that you could tell their stories?

Each book is different. Sometimes I get a sense of the character first, and then the story arrives in that voice; other times a story emerges and the characters make themselves known through what happens to them and how they respond to it.

Keesha’s House was your first novel written in verse. Since its publication, you have also written Spinning through the Universe: A Novel in Poems from Room 214, The Braid, Diamond Willow, Crossing Stones, Hidden, and most recently, Salt in verse format. How did you decide on this approach to novel writing?

I began as a poet, and the novels came out of the poetry. For many writers, it’s the other way around–they are novelists first, and then the poetry comes out of what the novel seems to need. For me, still, each novel emerges from careful attention to language, including the form, the sound, and the imagery, things I first learned through poetry.

Salt gives the reader a window into the War of 1812, told in the alternating voices of two 12 year old boys, one the son of an American trader and the other a Miami Native. James’ verse is in the horizontal lines of the American flag. Anikwa tells his story in the distinctive diamond patterns of Miami artwork. The two forms weave a story of two boys caught in a struggle for power, forced to choose paths and negotiate a world of human misconception, greed, tragedy and generosity. The visual form of this novel is a powerful storytelling tool. How did you come up with the idea to tell the story in this format?

The forms are interesting, aren’t they? So much of what has been imposed on the American landscape, especially in the Midwest, is based on Cartesian geometry–the grid work of road systems, calendars, soldiers marching in formation. James’ poems reflect this, but I didn’t want them to be overlaid on Anikwa’s poems, which have more of a pulse to them, like rivers, seasons, growing things.

The forms are interesting, aren’t they? So much of what has been imposed on the American landscape, especially in the Midwest, is based on Cartesian geometry–the grid work of road systems, calendars, soldiers marching in formation. James’ poems reflect this, but I didn’t want them to be overlaid on Anikwa’s poems, which have more of a pulse to them, like rivers, seasons, growing things.

I was pleased when I found the two forms for the two different characters, but I didn’t know at first how well they would work together. I came to see it as something like basket weaving, each element essential to the other.

Do you plan to write more historically based novels in verse like Salt, The Braid and Crossing Stones? What are you working on now?

Historical fiction is really hard. I tend to switch back and forth because it takes so long to do the research and make decisions about how much historical detail to include (enough to make the story authentic and compelling, but not so much that it weighs down the story, or is too complex for children to understand).

I’m working now on two more collaborations with Rick Lieder: Sweep Up the Sun, to be published spring, 2015, is about birds and Among a Thousand Fireflies, scheduled for spring, 2016, is about fireflies (titles can always change, of course). My next novel-in-poems, Applesauce Weather, is for early readers, and will be lightly illustrated. More than my other books, this one arose pretty directly from childhood memories.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to learn how to be a good writer?

What advice would you give to someone who wants to learn how to be a good writer?

Read a lot, of course, and establish a daily writing routine. I usually suggest taking classes to begin with, and finding a good critique group until you have an editor to work with. Even after you have an editor, a critique group is helpful in a different way. A small group of 4-6 friends you can trust is usually about right.

If you could switch places with anyone in the world for one day, who would it be and what would you do?

Maybe I’d switch places with a friend who is in prison, to give him a day of freedom and security.

Anything else we should know about you?

I loved insects as a child; monarch butterflies were, and still are, my favorite. Now my yard is a “monarch way station” which means I plant milkweed and nectar flowers for the monarchs. I am very worried about the monarch population decreasing because we are killing the milkweed they need, in order to make it easier to grow corn–more and more every year, for fuel as well as food.

In each of my books, I’ve consulted with people about the history and cultural background of the story, and those people have become friends, if they weren’t friends before. I am very lucky in the rich diversity of my friends and family, and I try to share that richness with my readers.

Learn More about Helen Frost on her website

Find her most recent book Salt: A Story of Friendship in a Time of War

Horses at Midnight Without a Moon

Jack Gilbert

Photo by Benny Necromundo

Our heart wanders lost in the dark woods.

Our dream wrestles in the castle of doubt.

But there’s music in us. Hope is pushed down

but the angel flies up again taking us with her.

The summer mornings begin inch by inch

while we sleep, and walk with us later

as long-legged beauty through

the dirty streets. It is no surprise

that danger and suffering surround us.

What astonishes is the singing.

We know the horses are there in the dark

meadow because we can smell them,

can hear them breathing.

Our spirit persists like a man struggling

through the frozen valley

who suddenly smells flowers

and realizes the snow is melting

out of sight on top of the mountain,

knows that spring has begun.

More poetry by Jack Gilbert

The River Between Us

Richard Peck

“Imagine an age when there were still people around who’d seen U.S. Grant with their own eyes, and men who’d voted for Lincoln.” Fifteen-year-old Howard Leland Hutchings visits his father’s family in Grand Tower, Illinois, in 1916, and meets four old people who raised his father. The only thing he knows about them is that they lived through the Civil War. Grandma Tilly, slender as a girl but with a face “wrinkled like a walnut,” tells Howard their story. Sitting up on the Devil’s Backbone overlooking the Mississippi River, she “handed over the past like a parcel.” It’s a story of two mysterious women from New Orleans, of ghosts, soldiers, and seers, of quadroons, racism, time, and the river. Peck writes beautifully, bringing history alive through Tilly’s marvelous voice and deftly handling themes of family, race, war, and history. A rich tale full of magic, mystery, and surprise. — Kirkus Reviews

More about The River Between Us

Singing Ringing Tree

Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu

Photo by Craig Rodway

Erected in the Pennine hills in Lancashire, England, the Singing Ringing Tree is constructed of galvanized steel pipes which use wind energy to produce music.

Learn more about the Singing Ringing Tree

Visit the Tonkin Liu Website

Healing Quote of the Day

Photo by Fort Vancouver National Trust

We realize the importance of our voice when we are silenced. — Malala Yousafzai

More about activist Malala Yousafzai