January First

Michael Schofield

A Child’s Descent into Madness and Her Father’s Struggle to Save Her

“A brilliant and harrowingly honest memoir, January First is the extraordinary story of a father’s fight to save his child from an extremely severe case of mental illness in the face of overwhelming adversity.” -Goodreads

It is every parent’s objective to keep their child safe and to provide them the tools to find happiness. For Michael Schofield, this goal became a desperate dream on the day his 6 year old daughter, “Jani”, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Jani’s erratic and often harmful behavior takes the family on a dizzying and frustrating journey to find correct diagnosis and effective treatment. Beneath the fear, heartbreak and anger over the disease and the lack of available resources, is the unrelenting love of two parents, Michael and Susan Schofield, who learn to live for the moments - moments where I see her smile, moments when I have hope, moments when I feel at peace with our future, whatever might come our way.

Learn more about January First here.

Follow Jani’s Journey on Michael Schofields’s blog.

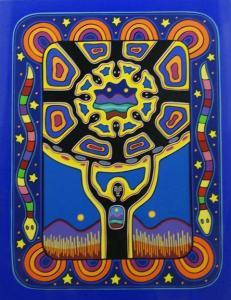

The Crown of Sunflower

Artist Victor Wang

Victor Wang is an award winning artist who teaches fine arts at Fontbonne University in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I grew up amongst the sunflower fields in northern China. In my childhood years, I played under the bright, yellow sunflowers with my brothers everyday. China’s Cultural Revolution played an important part in my life. During that time, sunflowers were used as political allegories to depict how citizens of China should follow Mao who represented the sun, since sunflowers follow the sun’s movements. People eventually inferred the deception that this symbol masked. After graduating from high school, I was sent to a labor camp in the country for ‘reeducation’ during China’s Cultural Revolution. There, I was subject to grueling farm work. Often, I worked in corn and sunflower fields from sunrise to sunset. Thus, for me, sunflowers evoke both personal joy and sadness.”Learn about Victor Wang and view more of his paintings on his website.

Music Therapist Wendy Zieve

As a child, singing at summer camp was such a powerful experience of joy and unity,

it interested me in the power of music.

Wendy Zieve grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and learned about music therapy at a career day in high school. She received her bachelor’s degree in Music Therapy at Michigan State and her masters at Lesley University in Boston. A certified music education teacher, she has taught in elementary schools and preschools for over 15 years. Wendy provides music therapy to address a variety of needs, including illness, dementia, Down syndrome, autism and physical disabilities. She also teaches college level courses in Music Therapy to other educators. Wendy lives with her family in Seattle, Washington.

Wendy, thank you for joining Healing Hamlet! What first drew you to music and to the field of music therapy?

As a child, singing at summer camp was such a powerful experience of joy and unity, it interested me in the power of music. I played piano while growing up in Wisconsin and heard about music therapy at a Careers Day at my high school. I had done some volunteer work with developmentally delayed children, and it seemed a great way to integrate my interests.

Can you tell us more about music therapy and its purpose?

Music therapy is an established health profession in which music is used within a therapeutic relationship to address the physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals. By creating, singing, moving, or listening to music, a range of abilities in each client is brought into focus. There are over 80 U.S. colleges that offer degrees in music therapy, and many do research on the benefits of music therapy for autism, stroke patients, mental illness, dementia, and other medical issues.

What sort of responses have you witnessed during music therapy sessions with students or clients?

I provide music therapy to several adult family homes serving seniors with dementia, where I use music to engage the residents socially, expressively, mentally and physically. Very often persons who have lost speech perk up and sing, or will get out of their chairs to dance.

I also work in respite care, private practice and school settings with individuals who have autism.

Music is often a preferred activity and a strength for persons with autistic spectrum disorders. In some cases they can answer questions and follow directions when they are sung but not when they are spoken. It is because music is processed in the brain in pathways that are different than speech.

The purpose of music therapy is to provide healing and therapeutic treatment for a variety of conditions. As a therapist, do you find the process of music therapy to be healing and therapeutic for yourself?

I always find that making music in a group is an instant way to connect, socially interact, and to feel whole.

You also teach music to preschoolers. How does teaching small children differ from providing music therapy to the elderly and disabled? How is it the same?

Early childhood is such an important time in every area of development – and a music class is a perfect time to foster social skills, emotional identification and regulation, fine and gross motor skills and listening skills. These developmental goals are sometimes the remedial goals that clients who have impairments are working on, although highly individualized in their treatment plans.

Where would you like to see the field of music therapy in the future?

Undoubtedly the research that is being done will propel the field forward – with the most exciting findings in rehabilitation and neurology, such as recovery from stroke and speech disorders. Representative Gabby Giffords in her recovery from bullet wounds, regained her speech by singing first with a music therapist who was trained in Melodic Intonation Therapy.

Increasingly across the country, insurance is covering music therapy with a doctor’s referral. Music therapy should be provided in all settings for people with developmental disabilities, autism, in rehab, in cancer wards, hospice, dementia and mental health.

Unfortunately, the state of Washington is decades behind the rest of the country in recognizing the profession of music therapy and providing access to services. An entire state recognition plan is underway involving legislation. Then funding for services will be another hurdle. The very first degree program is new at Seattle Pacific University, which will help to spread awareness through the student practicums.

Anything else we should know about music therapy?

There are many people calling themselves music therapists who are not board certified. This has led to lots of confusion with sound healing and bedside harpists. There is a rigorous curriculum that must completed at an accredited university, plus practicums, plus a 1200 hour internship, and then one must pass a board certification exam to get the title of MT-BC (Music Therapist – Board Certified). That is the gold standard that I wish employers were aware of.

What music and musicians do you find healing or inspiring?

My personal favorite type of music is jazz, and swing. For pain management, I listen to chanting form spiritual traditions – Buddhist/Hindu/Sufi.

In studies related to pain management, anything under the sun can be used as long as it works for that patient. What is relaxing for one might agitate another, so whatever works for the individual. In working with clients I’ve needed to know Christian hymns, Greek music, songs from the 1920′s, Hawaiian, Rock and Roll, Country, – you name it.

Wendy, thank you for sharing your knowledge about music therapy and for being an advocate for this field of healing.

To learn more about Music Therapy visit: The American Music Therapy Association, The Music Therapy Association of Washington and The Certification Board for Music Therapists

Keep up with Wendy on her website.

Blessed are the Cheesemakers

A Novel by Sarah-Kate Lynch

This sensuous and celebratory first novel is luscious in every way imaginable, a book to dip into eagerly and consume with much gusto. It is the story of two emotionally damaged people whom fate has dropped on a small cheese-making farm in Ireland. Kit Stephens’ fast track in New York City has quite suddenly screeched to a halt, and friends have sent him to Ireland to make sense of his life. Abbey Corrigan is lost when her marriage to a not-so-good-doer on a tropical island has left her with no place to go but her barely remembered grandfather’s cheese farm. In a story and style reminiscent of Steven Nightingale or Tom Robbins, the cheese and the cosmos and a cheese maker named Fee conspire to bring these two saddened souls to a storybook ending. Where other writers might overdo the magic realism or fairy-tale aspects of such an unfolding, Lynch proves to be gentle handed. This novel is a delight.

-From Booklist

Heritage

Artist Sally Morgan

An internationally recognized artist from Australia, Sally Morgan did not learn she was of Aboriginal descent until she was fifteen. Her artwork embraces her Aboriginal identity and heritage. She has also won the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission Award for Literature for her books, My Place and Wanamurraganya. Her artwork and writings provide a healing response to racism and discrimination.

Learn more about Sally Morgan here.

On the Pulse of Morning

“Here, root yourselves beside me.I am the tree planted by the river,

Which will not be moved.

I, the rock, I the river, I the tree

I am yours–your passages have been paid.

Lift up your faces, you have a piercing need

For this bright morning dawning for you.

History, despite its wrenching pain,

Cannot be unlived, and if faced with courage,

Need not be lived again.

Lift up your eyes upon

The day breaking for you.

Give birth again

To the dream.

Women, children, men,

Take it into the palms of your hands.

Mold it into the shape of your most

Private need. Sculpt it into

The image of your most public self.

Lift up your hearts.

Each new hour holds new chances

For new beginnings.

Do not be wedded forever

To fear, yoked eternally

To brutishness.

The horizon leans forward,

Offering you space to place new steps of change.

Here, on the pulse of this fine day

You may have the courage

To look up and out upon me,

The rock, the river, the tree, your country.

No less to Midas than the mendicant.

No less to you now than the mastodon then.

Here on the pulse of this new day

You may have the grace to look up and out

And into your sister’s eyes,

Into your brother’s face, your country

And say simply

Very simply

With hope

Good morning.”

-Excerpt from On the Pulse of Morning by Maya Angelou

Brighter than the Sun

Colbie Caillat

“Oh, we could be the stars, falling from the sky Shining how we want, brighter than the sun.”Author Carole Estby Dagg

Instead of writing books, I became a librarian, surrounding myself with books other people had written. Clara and Helga’s story kept nagging me, though, so for their sake I decided to risk rejection. If they had repeatedly risked their very lives to prove women could walk across the country on their own, how could I be afraid of something as innocuous as a rejection letter?

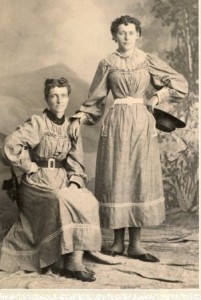

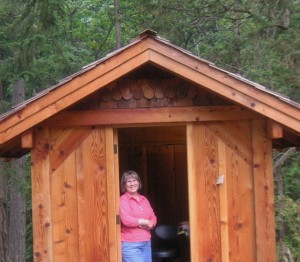

Carole Estby Dagg is the author of The Year We Were Famous, the story of her great grandmother and great aunt’s walk across America in 1896. As a child, books served as loyal companions to Carole as the family moved a dozen times due to her father’s career as a construction engineer. She has worked as a CPA, children’s librarian, and assistant library director. Married with two grown children and two grandchildren, she writes in Everett,Washington and in a converted woodshed on San Juan Island under the supervision of her bossy cat.

Carole, thank you for visiting with Healing Hamlet! Please tell us what inspired you to write The Year We Were Famous? Why do you feel the story of these women needed to be told?

Newspapers repeatedly reported that Clara and Helga intended to write a book about their adventures, but because of the way the trip ended, all their records were burned and the family agreed never to talk about the trip again. Times change. What was considered scandalous back in 1896 would be considered heroic today. It was time their story was told.

It seems that fate had decided long ago that I would be the one to tell that story. I found out after the book launched that I had been the only child allowed into the hospital to see Great-aunt Clara before she died.

It was a long journey from the inception of your book to its publication. During the process did you feel a connection to your great aunt and great grandmother and their own journey?

I didn’t inherit Clara and Helga’s extraordinary physical strength – I can’t imagine walking 25-40 miles a day, day after day for seven and a half months. I did inherit the perseverance gene though. I took each rejection as a sign that I needed to try another approach, or that I needed to work more on craft. During the fifteen years of rejections, I rewrote the book from Helga’s point of view, Clara’s point of view, as diary, as narrative, first person, third person, at least a dozen or more complete re-writes. I also took eight college-level writing classes and attended at least a dozen workshops. Just as they kept focused on their goal, one step at a time, I kept writing and re-writing, one word at a time, until I found a publisher.

Before the publication of your book, you won the Sue Alexander Award for most promising new work. The prize provided you with a flight from Washington State to New York City. After the years you dedicated to the story of your ancestors’ 232 day trek across that same distance, what were your thoughts during that trip?

The flight to New York was a blur. What really aroused my empathy for Clara and Helga on their trek was a road trip with my daughter, driving part of the route that Clara and Helga took across the country. As we drove hundreds of barren miles across Wyoming, I thought about how desperately alone Clara and Helga must have felt, sleeping in the open and walking for days without seeing another person.

The women in your book began their journey as a way to stave off financial ruin. There is also the perception that your great-grandmother suffered bouts of depression. How was this journey healing for these women? How can the story be healing for the reader?

The book started as an episodic adventure story, based on newspaper accounts of their survival of flash flood, attack, Indian encounters, being lost for days without food or water, and meeting President-elect McKinley. What my first editor at Clarion, Jennifer Wingertzahn, made me realize was that this was also a mother-daughter story describing how a mercurial, outgoing mother and methodical, shy daughter would come to understand and forgive each other during the time they were yoked together for the 232-day trek.

What had always inspired me, growing up and hearing snippets of the story, was not that they came home empty-handed, but that they did it: They walked four thousand miles, relying only on themselves, their faith, and the kindness of strangers. They did not give up, but kept headed toward their goal of New York City by putting one foot in front of the other, for eight million steps, until they reached their goal. The New York World wrote that they expected to write a book “if they survived.” They did survive, despite public opinion that the trek was impossible. I hope the book inspires readers to persevere toward their goals too.

How would you describe the internal process of writing this book? Was the experience healing for yourself?

My grandmother predicted that I would grow up to be a writer, but I had convinced myself that I didn’t have innate writing talent and I would be setting myself up for disappointment if I tried. Instead of writing books, I became a librarian, surrounding myself with books other people had written. Clara and Helga’s story kept nagging me, though, so for their sake I decided to risk rejection. If they had repeatedly risked their very lives to prove women could walk across the country on their own, how could I be afraid of something as innocuous as a rejection letter? Over a period of fifteen years, I collected 29 rejection slips, but I kept revising and resubmitting. I was finally accepted by my first choice publisher, Clarion/Houghton Mifflin, a house that had rejected me twice before.

As a librarian and book lover, how have you witnessed books to be healing?

For children and teens especially, books offer a risk-free way to have adventures and experience other lifestyles and periods of history. In books, readers may discover characters facing problems similar to their own, and see how those characters faced challenges such as divorce, death of a parent, bullies at school, or having to eat at the outcasts’ lunch table. Readers can also gain perspective and strength by reading about characters, real and fictional, who faced problems far greater than their own.

What is your next project?

I wrote a sequel to The Year We Were Famous which imagines how Clara adjusted to her tragic homecoming in 1897 and broke into the man’s world of business, but haven’t found a publisher yet. I’m also working on a book set in Alaska Territory during the Great Depression.

What books and writers do you find inspiring?

As a child moving every few months, my constants were my two sisters and the friends I made in books. Wherever we moved, I could reunite myself with Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy, Tacy and Tib or Elizabeth Enright’s Melendy series. My real life friends lasted only the few months I was in town, but my book friends were always waiting for me in the next library. The characters in those books demonstrated how love and friendship can withstand challenges and the mistakes imperfect people make.

Carole, thank you so much for telling the story of Helga and Clara, and for sharing your own inspiring story with Healing Hamlet!

Learn more about The Year We Were Famous and Carole Estby Dagg on her website.